Urea Phosphate. A safe source of urea

In Solution U-Phos

A slow release urea and soluble phosphorus

This compound has unique properties that make it highly desirable in the formulation of soluble supplements and licks. Urea Phosphate is a stable combination of urea and phosphorus, containing 18 % Nitrogen and 44% P2O5 (19% P). It is rapidly soluble and is an excellent source of nitrogen and phosphorus for water supplementation of sheep and cattle and adding to molasses or licks.

It is a slow release form of urea. This is due to the strong bond between the urea molecule and the phosphoric acid molecule that must be broken before urease can act on the urea. Slow release forms of urea have been shown to increase performance in feedlot cattle.

Urea, on its own, is unstable in alkaline water and will break down to Ammonia and be lost to the atmosphere. Urea Phosphate is strongly acidic (pH 2) and acts to buffer the high bicarbonate bore waters, thus stabilising urea and slowing its decay to ammonia. By reducing pH, any Ammonia (NH3) is converted to Ammonium (NH4) which is stable, as well as non-toxic. Urea is rapidly broken down in the rumen (in seconds) by the enzyme urease. The resultant ammonia release is what is toxic when high blood levels affect the brain. Urea phosphate is not broken down by urease and does not release large quantities of ammonia and si non-toxic.

It is completely and rapidly soluble and ideal for water supplementation and mixing in molasses or licks.

Slow Release Urea

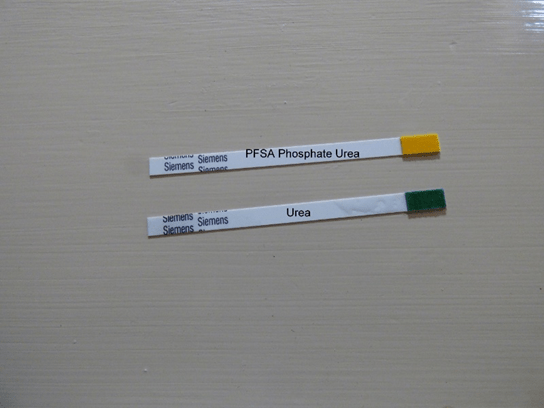

To demonstrate the slow release features of Urea Phosphate, a simple test, using a urea test strip has been used. These strips contain the enzyme urease to breakdown the urea to ammonia and it only takes 60 seconds to do this.

In the picture below one strip has been exposed to a solution of urea at the rate of 1 gram per litre.

A second strip has been exposed to urea phosphate at 5 grams per litre. As shown, the Urea strip has turned a deep green, showing 1 gram per litre of Urea, while the Urea Phosphate strip is unchanged showing that the urea is protected from breakdown by the urease enzyme. The urease has no effect in converting urea phosphate to ammonia thus making it a safe form of urea. The conversion occurs slowly as the bacteria release the phosphorus bond before attacking the urea molecule. Urea Phosphate is a safe form of urea and will not cause urea poisoning.

In terms of the speed of breakdown of urea to ammonia, all of the urea in the urea only mix was converted to ammonia within 60 seconds. For the urea phosphate none of the urea was converted as the urea was not available to the urease enzyme and the enzyme action was reduced in the acid environment

The Importance of P in ruminants

The signs of P deficiency in cattle are fairly well known, they include reduced appetite, general unthriftyness, body weight loss, poor growth, infertility, bone soreness (peg leg), bone fractures, bone chewing leading to botulism and death. Phosphorus restriction during late lactation and early pregnancy probably causes the most deleterious effects. Growth and fertility are severely reduced.

It is also well known that the daily requirement of adult breeders is around 20 grams of P per day.

What is not so well known is that the requirement of the rumen bacteria for P may be higher than the cows! It has been reported that the rumen microbes require approximately 5 grams of P per Kg dry organic matter of feed or about 60 grams of P per day. If the P requirements of the rumen microbes are not met this will result in lower fermentation rates and decreased digestibility of organic matter. In other words the rumen microbes will not be able to adequately ferment what food there is available, be it of high quality or not.

When it is considered that under normal circumstances a high producing cow will recycle up 60 grams of P per day through the saliva, it gives an idea of the importance of P to the micro-organisms in the rumen. Any deficiency in dietary P will also result in lower salivary P. As salivary P is of prime importance to the micro-organisms this has severe effects of fermentation efficiency and even when there is good feed available fermentation will be reduced if there are limitations in available P. The P delivered utilised by the rumen bacteria must be in a soluble form to be utilised. Much of the P contained in some plant types and the less soluble inorganic sources must be absorbed via the small intestine and recycled via the saliva before being available to the rumen bacteria.

Any reduction in Organic Matter fermentation in the rumen leads to reduced feed intake. In fact, the first clinical sign of P deficiency is reduced appetite. Feed intake can also be reduced by low plasma P levels and as the demands of lactation will reduce plasma P levels even more there will be a greater restriction in feed intake.

While limitations of P reduce Organic Matter digestibility in the rumen it also affects microbes in the hindgut as well, thus reducing all microbial function. The large intestine, especially the caecum and colon, supports an active fermentation that is quite similar to that in the reticulo-rumen. The caecal-colonic fermentation may supply 10-15% of the gross energy available to a dairy cow. However, most microbial protein generated by this fermentation is lost via the manure.

Analysis of Urea Phosphate

Analysis:

Minimum Crude protein 112.5

Urea Equivalent 39.1

Nitrogen (N) Total 18.0

Phosphorus (P) as water soluble 19.2

The Cost

Urea Phosphate is completely utilised by the ruminant, both the P and N contributing to growth and as it is 100% soluble there is no wastage.

When comparing the cost of supplements, it is important to consider the cost of the available P. In most cases, Urea Phosphate will prove a very cost effective source of P and N as both of these compounds are 100% available. Other forms of P, such as Kynophos are insoluble and also only 60% available.